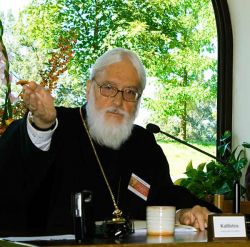

Lecture by Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia

The beauty that is the world’s salvation is indeed the uncreated beauty that shines forth on Tabor

The transfiguration of Christ

and the suffering of the world

1. The challenge of Ivan Karamazov.

Let us begin this afternoon with the question that Ivan Karamazov puts to his brother Alyosha in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s masterwork The Brothers Karamazov. “Suppose,” says Ivan, “that you are creating the fabric of human destiny, with the object of making people happy at last and giving them peace and rest, but that in order to do this it is necessary to torture a single tiny baby… and to found your building on its tears. Would you agree to undertake the building on that condition?”. To this Aloysha replies: “No, I wouldn’t.”

If we wouldn’t agree to do this, then why apparently has God done so? How are we to reconcile the tragic mystery of innocent suffering, present everywhere in the world around us, with our faith in a God of love? What, then, is to be our response to Ivan Karamazov?

You will note that, bearing in mind the distinction made by Gabriel Marcel, among others, I spoke just now about the “mystery” rather than the “problem” of evil and innocent suffering. A problem is an intellectual puzzle, a conundrum, which can be deciphered through clear thinking and logical acumen. But evil and innocent suffering, as a mystery, cannot be explained simply through rational argumentation. A mystery is something that has to be changed by action in order for it to become transparent to thought; something that can be resolved, if at all, only through personal experience, personal participation and compassion. We cannot begin to understand suffering unless we are directly involved in it.

Such precisely is the meaning of the crucifixion: God in Christ is victorious over evil because in His own person He suffers to the full all its consequences, without any reservation whatsoever. Vincit qui patitur. Our God is an involved God: “Having loved His own who were in the world, He loved them to the utmost” (John 13:1).

Approaching this mystery of suffering and evil, seeking to add to Alyosha’s brief and enigmatic reply, let us recall the words found in another of Dostoevsky’s novels, The Idiot: “Beauty will save the world.” We shall not begin to understand suffering without being involved in it; but we are not to allow such involvement to make us forget the presence, within this fallen world, of divine and saving Beauty. What, then, does beauty tell us about the salvation of the world? Are Dostoevsky’s words simply escapist? When we watch a child in Africa dying of starvation, or see a hostage tortured and shot in Iraq, what sense does it make to speak of “beauty”? Or has Dostoevsky offered us a vital clue?

The supreme occasion on which the divine Beauty has been revealed to humankind is the transfiguration of Christ on mount Tabor. As the Orthodox Church affirms in one of the hymns at Vespers for the feast:

Transfigured today upon Mount Tabor before the disciples,

In His own person He showed them human nature

Arrayed in the original beauty of the image.

What light, then, is shed upon the mystery of suffering by the divine beauty of the Christ transfigured? What kind of connection is there between the glory of Mount Tabor and the world’s anguish and despair?

2. “A glory brighter than light.”

Let us begin by considering the nature of this glory disclosed on Tabor, and then explore the relationship between the two hills, Tabor and Calvary. What, first, is the nature of the radiance that shone as lightning from the Saviour’s face and clothes at his transfiguration? And what, second, is the connection (if any) between the glory of the transfiguration and the kenosis of Christ at Gethsemane and Golgotha?

As regards the light of transfiguration, in the Gospel narrative it is said that Christ’s face shone “as the sun” (Matthew 17:2). Here the Greek Fathers and the Orthodox liturgical books are more explicit and emphatic. The Lord’s face, says St John Chrysostom, shone not merely as but more than the sun. The glory of Tabor, so the Fathers teach with striking unanimity, is not merely a natural but supernatural light; not merely a material, created luminosity but the spiritual and uncreated splendour of the Godhead. It is a divine light. Already in the late second century Clement of Alexandria explains that the apostles did not see the light by virtue of the normal power of sense perception, for physical eyes cannot see the light of the Godhead unless transformed by divine grace; the light is “spiritual” and is disclosed to the disciples, not in its entirety, but only so far as they are capable of perceiving it. Exactly the same is stated in the Troparion (apolytikion) of the feast:

Thou wast transfigured upon the mountain,

Showing the glory to Thy disciples as far as they were able to bear it…

It is, says St Gregory the Theologian, a light “too fierce for human eyes,” a light, in the words of St Maxim the Confessor, that “transcends the operation of the senses.”

Similar statements recur throughout the liturgical texts for the feast. The light of Tabor, it is said, is “non-material,” “eternal,” “infinite,” “unapproachable,” “a glory brighter than light.” In short, it is nothing less then “the glory of the Godhead;” “it is a radiant and divine splendour.” As St Dionysios the Areopagite affirms, the light is “supraessential” or “beyond being” (hyperousios). When in the fourteenth century St Gregory Palamas insisted that the light of Tabor is identical with the uncreated energies of God, he was doing no more than summarize the existing tradition of the Fathers, extending back more than a thousand years before him.

Concerning this uncreated, non-material light that shines from the transfigured Saviour, at least four things may be affirmed:

It reveals to us the glory of the Trinity;

It reveals to us the glory of the Christ as God incarnate;

It reveals to us the glory of the human person;

It reveals to us the glory of the entire created cosmos.

First, the light of Tabor is a light of the Holy Trinity. As the Church sings at Vespers of the feast:

Christ, the light that shone before the sun,

This day has mystically made known upon mount Tabor

The image of the Trinity.

Seen as a Trinitarian celebration, the feast of the Transfiguration is closely similar to the feast that occurs exactly eight months previously, Theophany or Epiphany (6 January), the celebration of Christ’s baptism. Both are feasts of light: indeed, Theophany is commonly called in Greek as Ta Phota, “The Lights.” But the parallel extends further than this: both are occasions in which is plainly manifested the joint action of the three persons of the Godhead. At the baptism of Jesus the voice of the Father speaks from heaven, bearing testimony to the beloved Son, as the Spirit in the form of a dove descends from the Father and rests upon Christ (Mark 1:9-11). Precisely the same triadic configuration is evident on Mount Tabor: the Father speaks from heaven, testifying to the Son, while the Spirit is present on this occasion not in the form of a dove but as a cloud of light.

Viewing the transfiguration, then, in this Trinitarian perspective, we proclaim at Matins in the exaposteilarion:

Today on Tabor on the manifestation of Thy light, O Logos, …

We have seen the Father as light

And the Spirit as light,

Guiding with light the whole creation.

While Trinitarian, the glory of the transfiguration is, in the second place, more specifically a Christological glory. The uncreated light that shines from the Lord Jesus reveals him as “true God from true God… consubstantial with the Father,” in the words of the Creed. But at the same time on Tabor the Lord’s human body, although radiant with non-material glory, still remains genuinely material and human; his created flesh is rendered translucent, so that the divine glory shines through it, but it is not abolished or swallowed up. As the hymnography of the feast expresses it, employing the language of the Calcedonian definition and the Fifth Ecumenical Council, Christ is revealed upon the mountain as “one from two natures, and in both of them complete.”

Interpreting the Christological implications of the transfiguration, we may say: nothing is taken away, and nothing is added. Nothing is taken away: transfigured on Tabor, Christ still remains fully human. Yet equally nothing is added: the eternal glory revealed on Tabor is something that the incarnate Christ possesses always, from the very first moment of his conception in the womb of the Holy Virgin. This glory is with him throughout his earthly life: even during the moments of his deepest humiliation, as at the agony in the garden of Gethsemane or at the cry of dereliction upon the cross, it still remains true that “in him dwells all the fullness of the Godhead bodily” (Colossians 2:9). The difference lies simply in this: at other points in his life on earth the glory, although truly present, is hidden beneath the veil of the flesh; on the mountain-top, for a brief instant, the veil grows transparent and the glory is partially made manifest.

At the transfiguration, however, no change occurred in Christ himself; the change came rather in the apostles. In the words of St John of Damascus, “He was transfigured, not by assuming what he was not, but by manifesting to his disciples what he was, opening their eyes.” “He did not at that moment become more radiant or more exalted,” says St Andrew of Crete, “far from it: but he remained as he was before.” As Paul Evdokimov expresses it, “The Gospel story speaks not about the transfiguration of the Lord, but about of the apostles.”

The feats of transfiguration, then, sets before us the saving paradox of our Christian faith: that Jesus is entirely God and at the same time entirely human, yet he is one single person and not two. Each year, on 6 August, we do well to reflect with the utmost vividness and humility upon this double fullness in the incarnate Saviour: upon the perfection of his Godhead and the undiminished integrity of his manhood.

Thirdly, the transfiguration reveals to us not only the glory of the Trinity, not only the glory of Christ, one person in two natures, but also the glory of our own human personhood. The transfiguration is a disclosure not simply of what God is but equally of what we are. Looking at Christ transfigured upon the mountain, we see human nature – our created personhood –, taken up into God, filled entirely with uncreated life and glory, permeated by the divine energies, yet still continuing to be totally human. We see human nature as it was at the beginning, in Paradise before the fall; we see human nature as it will be at the end, in the age to come after the final resurrection – and this last state of human nature is incomparably higher than the first. Transfiguration is in this way eschatological in character; it is, in the words of St Basil the Great, “the inauguration of Christ’s glorious parousia.”

The transfiguration of Christ therefore shows us, according to St Andrew of Crete, “the deification of human nature.” If we wish to understand the true meaning of the doctrine of theosis, then let us attend a vigil service for the feast of the transfiguration, and listen attentively to what is said and sung. Christ, transfigured on the mountain, reveals to us the full measure of our human potentialities, the ultimate capacity of our human nature at its truest and highest. In the words of the kontakion for the forefeast:

Today, in the divine transfiguration,

All human nature shines forth divinely

And cries aloud with gladness.

Nor is this all. Fourthly, – and this has a particular significance for the contemporary world – the transfigured Christ reveals us the glory not only of the human person but equally of the whole material creation. “Thou hast sanctified with Thy light all the earth,” as we sing at vespers for the feast. The transfiguration is cosmic in its scope; for humanity is to be saved not from the world but with the world. Mount Tabor anticipates the final state foretold by St Paul, when the creation in its entirety “will be delivered from boundage to corruption,” and will enter into “the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (Romans 8:21). It is the inauguration of the “new earth,” of which the Apocalypse speaks (Revelation 21:1).

On the mountain, that is to say, we see not only a human face transfigured with glory; the radiance shines equally from Christ’s clothes (Matthew 17:2). The light of Tabor transforms not only the body of the Saviour in isolation, but also the other material objects associated with him, the man-made clothing that he wears; and so, by extension, potentially, it embraces all material things. Not only each human face but also each physical object is capable of transfiguration. In the light of that one face which was altered, of those particular clothes that were rendered white and glistering, all human faces have acquired a fresh radiance, all common things, have been given new depth. In the eyes of those who truly believe in the transfigured Christ, nothing whatever is mean or despicable; all created things can become a vehicle of God’s uncreated energies. The glory of the burning bush is all around us, wanting to be unveiled. The feast of the transfiguration is par excellence an ecological celebration.

3. The two hills Tabor and Calvary.

It is time to return to our original question. In what way does the glory of Christ transfigured upon the mountain – glory of the Trinity, glory of the Logos incarnate, glory of the human person, glory of the whole creation – enable us to understand the mystery of suffering? How does it help us to respond to the anguish, anger and despair that our sisters and brothers feel in Iraq or Darfur, or for that matter in Milan and Turin, or in my own-town of Oxford? It is all very well, you may say, to speak about the glory of burning bush that is all around us; but how can we make these words a living reality?

An answer, or at least the first beginning of an answer, emerges if we consider the context in which Christ’s transfiguration occurred. It took place shortly before Jesus departed from Galilee (Matthew 19:1) in order to journey for the last time up to Jerusalem. So the next major events after the transfiguration are the meeting with Zacchaeus in Jericho (Luke 19:1-10), the raising of Lazarus in Bethany (John 11:1-44), and then the entry into the Holy City, followed almost immediately by the crucifixion. Thus chronologically there is a close proximity between the transfiguration and the passion. This is easily overlooked, because in the Church calendar Holy Week and the feast of transfiguration (6 August) are celebrated at entirely different moments in the year. If, however, our liturgical observance were to adhere more closely to the actual sequence of events, then we would commemorate the transfiguration at some points during Lent; and in fact according to the Latin rite the Gospel for the second Sunday in Lent is precisely the Matthean account of the transfiguration (Matthew 17:1-9).

Let us, then, attempt to explore further the possible connection between the two hills: Tabor and Calvary. This can best be done by asking: in the Gospel narrative, what comes immediately before the description of Christ’s transfiguration, and what comes immediately afterwards?

In all three Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, there is an identical sequence of events. First, on the road to Caesarea of Philippi, Peter makes his decisive confession of faith: “You are the Christ, the son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16). Jesus goes on to predict his coming passion, death and resurrection (16:21). Peter is scandalized, but Christ rebukes him and insists that not only he himself but all who desire to be his disciples are called to follow him on the path of voluntary suffering: “If anyone wants to come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me” (16:24). Discipleship means cross-bearing. Christ then foretell his future coming in glory (16:28), and after that there follows immediately the account of the transfiguration: “After six days Jesus took Peter, James and John his brother, and led them up a high mountain by themselves” (17:1).

This sequence in the Gospel narrative is not simply a chance juxtaposition, but expresses a vital and all-important spiritual interdependence. First and most obviously, the transfiguration endorses Peter’s confession of faith: Jesus is indeed not only son of man but “son of the living God.” Tabor vindicates Peter’s proclamation of Christ’s divinity. But the transfiguration is also to be understood in the light of the remainder of the dialogue on the road to Caesarea of Philippi. It is no coincidence that our Lord should speak about his passion and the universal vocation of cross-bearing immediately before the revelation of his divine glory on Tabor. On the contrary, he is concerned to emphasize the essential connection in his redemptive economy between glory and suffering.

So the context of the transfiguration suggests to us a possible way of approaching the mystery of innocent suffering. Glory and suffering go together in Christ’s saving work. The two hills, Tabor and Calvary, are indeed significantly linked. The transfiguration cannot be understood except in the light of the cross, nor can the cross except in the light of the transfiguration, and likewise of the resurrection.

This becomes clearer as we look more closely at the Gospel narrative. Who, we may ask, are the three disciples who accompany Jesus to the mountain-top? They are Peter, James and John. And who are the three disciples present with Jesus at Gethsemane? Exactly the same three: Peter, James and John (Matthew 26:37). It can of course be argued that these three were present on both occasions because they were the disciples most intimately associated with Jesus, an inner circle within the twelve. But surely there is to be found a deeper meaning than this.

Just as it is no coincidence that Christ should speak about cross-bearing immediately before his transfiguration, so it is no coincidence that the same three disciples are present both on the mountain-top and at the agony of the garden. Witnesses of his uncreated glory, they are witnesses also of his deepest anguish. Witnesses of the transfiguration, they are witnesses also of what Fr Enzo has called, in his opening address, the “defiguration.”

What, we may further ask, is the theme about which Moses and Elias converse with Christ as they stand with him in the radiance of Tabor? It is, according to St Luke, nothing else than his coming exodus at Jerusalem, his imminent death upon the cross (Luke 9:31). Is not this an astonishing fact? Enfolded in the light of eternity, they speak not about the transcendent joys of heaven but about the sacrificial kenosis of the crucifixion. This indicates exactly how the transfiguration is to be understood in the light of the crucifixion, and the crucifixion in the light of the transfiguration. On the summit of Tabor there is planted the cross; and equally behind the veil of Christ’s crucified and bleeding flesh upon Golgotha we are to discern the presence of the uncreated light of the transfiguration. Glory and suffering are aspects of a single, undivided mystery. “They crucified the Lord of glory,” affirms St Paul (1 Corinthians 2:8): Christ is as much Lord of glory when he dies upon the cross as when he is transfigured on Tabor.

This “Tabor-Calvary syndrome,” as it may appropriately be termed, is repeatedly underlined in the liturgical texts for 6 August. First of all, it is noteworthy that the feast of the transfiguration occurs forty days before the exaltation of the cross on 14 September. The number forty has obviously a special significance in sacred time: Israel spent forty years in the wilderness (Numbers 14:33), David and Salomon both reigned for forty years (1 Kings 2:11 and 11:42), Elias journeyed for forty days to mount Horeb before experiencing the theophany at the cave (1 Kings 19:8), Jesus was tempted for forty days in the desert (Mark 1:13), and he ascended into heaven forty days after his resurrection (Acts 1:3). The fact that the feast of the transfiguration is exactly forty days before the exaltation of the cross is emphasized by singing the katavasiai of the cross at the Canon in Matins on 6 August. Comings events cast their shadows before.

This is by no means the only place in the liturgical observance of the transfiguration where Tabor and Calvary are juxtaposed. The first two stichera at Great Vespers, both describing the moment of transfiguration, begin strikingly with the words “Before Thy crucifixion, O Lord.” In the same spirit the first sticheron on the Praises at Orthros commences, “Before Thy precious cross and passion.” The link between transfiguration and crucifixion is stressed likewise in the kontakion of the feast:

Thou wast transfigured upon the mountain,

And Thy disciples beheld Thy glory, O Christ our God,

As far as they were able so to do:

That, when they saw Thee crucified,

They might know that Thy suffering was voluntary…

At the crucifixion, then, the disciples are to recall the theophany on Tabor, and they are to understand that Golgotha also is a theophany. Transfiguration and passion are each to be understood in terms of the other, and equally in terms of the resurrection.

The link between Tabor and Calvary is evident, not only in Scripture and in the liturgical texts, but equally in iconography. As Fr Enzo reminded us, in what is the earliest surviving representation of the transfiguration (along with the mosaic in the apse of St Catherine’s church, mount Sinai) – in, that is to say, the mosaic in the apse of St Apollinare in Classe at Ravenna – the transfigured Christ is shown precisely in the form of a crux gemmata, a vast jewelled cross extending across the firmament of heaven. The interconnection between the transfiguration and the passion is here proclaimed in a particularly striking and memorable fashion.

We have considered what happened immediately before the transfiguration. Let us now look at what comes directly afterwards. In all three Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, there is once more an identical sequence of events. The three disciples, descending with Christ from the mountain, are confronted at once by a scene of confusion and distress: a sick child, afflicted with epileptic fits; a father, crying out in anguish, “I believe: help my unbelief!”; the other disciples, bewildered and unable to assist him (Matthew 17:14-18; Mark 9:14-27). Once more, this is not a chance juxtaposition. Peter wanted to remain on the mountain-top, building three tabernacles and so prolonging the vision (Matthew 17:4). This Jesus will not allow: he insists that they descends once more to the plain. We participate in the grace of the transfiguration, not by isolating ourselves from the suffering of the world, but by involving ourselves in it. Our daily living is transfigured precisely to the extent that, each according to our own situation, we share in the pain, loneliness and despondency of those around us.

Such, then, is the life-giving connection between the glory of mount Tabor and the world’s anguish and despair; such is the message of the transfigured Saviour to the suffering human race; such is the significance of the transfiguration in the contemporary world. All things are capable of transfiguration, but such transfiguration is possible only through cross-bearing. As the Orthodox Church affirms each Sunday at Matins, “Behold, through the cross, joy has come to all the world.”

Through the cross: there is no other way. For Christ himself, and for all of us who seek to be members of his body, glory and suffering go together. In our life, as in his, the hills Tabor and Calvary form a single mystery. To be a Christian is to share, at one and the same time, in the self-emptying and self-sacrifice of the cross, and in the great joy of the transfiguration and the resurrection. Present with Christ in the glory of the mountain-top, we are present with him also in Gethsemane and Golgotha.

“The paradox of suffering and evil,” says Nicolas Berdyaev, “is resolved in the experience of compassion and love.” This is true not only of ourselves but of God incarnate. Our God is an involved God. He does not offer an answer in words to Ivan Karamazov’s question; his answer is an answer expressed in life, through his compassion, through his participation in our pain, through his suffering love. His transfiguration bestows healing upon us, exactly because it signifies not escape from the evil and alienation of the fallen creation, but an unreserved and open-ended involvement in it. The transfiguration leads to the cross, and the cross to resurrection: therein lies our unfailing hope.

The title of my address has been “The transfiguration of Christ and the suffering of the world.” But I could equally well have chosen as my title, “The suffering of Christ and the transfiguration of the world.” “Beauty will save the world:” yes, certainly, Dostoevsky was right. But Isaiah was equally right to say, “Surely he has borne our grieves and carried our sorrows” (Isaiah 53:4). The beauty that is the world’s salvation is indeed the uncreated beauty that shines forth on Tabor; but this same uncreated beauty is manifested no less in the sacrifice of the cross. Christ’s transfiguration does not enable us to evade all suffering, but it makes our suffering life-giving and creative: in Paul’s words, “… dying, and see, we are alive… sorrowful, yet always rejoicing” (2 Corinthians 6:9-10).

Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia